Single-Collector Museums, an Important Source

October 08, 2015

by Diana Greenwald | Filed in: Collectors

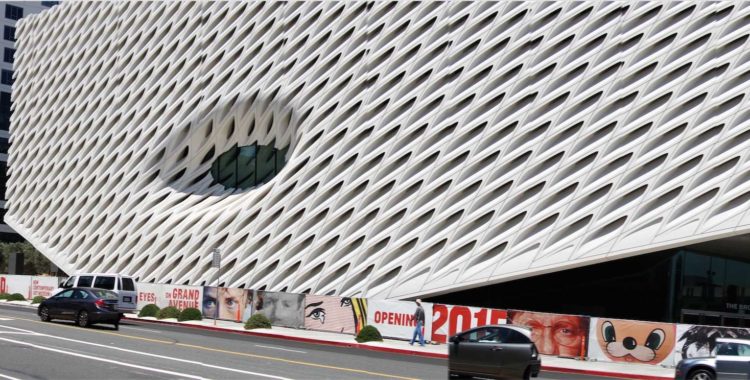

New York Times art critic Holland Cotter recently reviewed the new Broad Museum in Los Angeles, founded by billionaire contemporary art collector Eli Broad. The review—titled “The Broad is an Old-Fashioned Museum for a New Gilded Age”—invokes the actions and legacies of famous late nineteenth-century American collectors like Henry Clay Frick (of New York’s Frick Collection) and Isabella Stewart Gardner (of the eponymous Boston museum).

Cotter makes the comparison to claim that The Broad fails to “radically alter the old museum model…[and] shift its identity from locked treasure house to clearinghouse for fresh ideas.” While the critic considers this a count against the institution, the creation of a museum that “preserve[s] a private collection conceived on a masterpiece ideal” (in Cotter’s words) creates a useful resource for the student of art and economics.

Collectors play an essential role in the economics of art. Without their desire to patronize artists directly or purchase works on the secondary market, there would be no financial support for art, contemporary or historical. However, their economic role is not limited to artistic transactions. They are successful participants in the wider economy who have chosen to use their surplus income to sponsor the arts. In this way, they are an important contact point between broader social and economic conditions and the art world.

Single-collector museums like The Broad, the Frick, and the Gardner enshrine the tastes of a person who was at the heart of the economy at a given time. What does it mean that Broad—the self-made founder of two major companies—chooses to collect contemporary art while Gardner—a Gilded Age Boston Brahmin heiress—showed a strong preference for the Italian Renaissance? We can learn something about the economies and societies in which these people succeeded by studying how they spent their money. While museum collections that were formed by amateurs rather that generations of professionals might be stodgy, they demonstrate the full range of an individual’s eclectic preferences. They are a largely unedited sample of taste in a given moment and setting, which is a valuable scholarly source.

This is the first of four posts to be published throughout October and November that dedicated to the topic of patrons and collectors. Each post will highlight a different collector (or group of collectors) and discuss how their behaviors can shed light on interactions between the arts and economics in general.

Art & War: The Walters Museum >>

<< Resource Rewind: Canvases & Careers