Resource Rewind: Canvases & Careers

September 17, 2015

by Diana Greenwald | Filed in: Resources

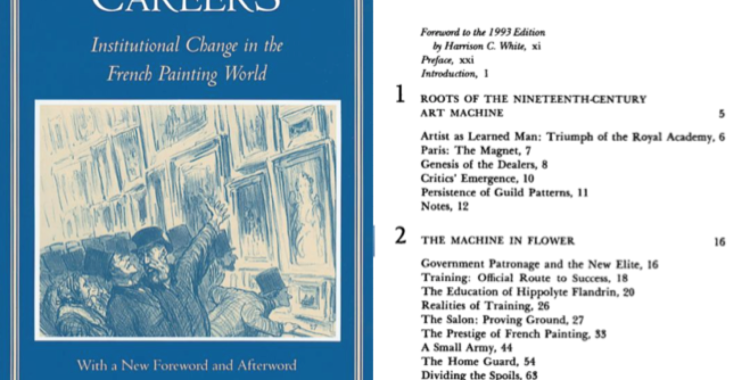

Harrison C. White and Cynthia A. White first published Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting World in 1965. It was reprinted in 1992 and continues to be a much-cited and much-discussed analysis of the art world. The book uses qualitative and quantitative analyses to track the transition of the French art world from a centralized academic system organized around the annual Paris Salon to the “dealer-and-critic system”, where production and success are more dependent on a decentralized commercial market. The Whites consider the Impressionists and their careers to be a critical inflection point in the history of art. They write: “The Impressionists seemed to mark a basic new era in art primarily because they ushered in a new structure for the art world. Let us call this institutional system the dealer-and-critic system.” (‘Introduction,’ 2) While the book is often cited just for this insight, it has many more points to offer about the changing nineteenth century art world and the role of the artist in this changing world.

“In the trend toward genre painting there was also an attempt to solve the problem of finding a secure career in painting. More and more genre painters specialized, taking a particular subject and making a career out of it.” (‘A New System Emerges,’ 92)

Changes in the content—and even size—of paintings during the nineteenth century have often been attributed to what economists call “demand effects.” Consumers and their preferences create changes in the market. The Whites offer a refreshing explanation that deals with the supply side. The art suppliers—artists—change their output to meet new market conditions. This, in turn, influences demand for art. Structural explanations like these are rare in the art historical literature.

‘Those who state that the decline of the aristocratic patronage system and its heir, the Academic system, led to the alienation of the artist from the modern world are only half right. The old system of financial support did become inadequate. but a new system took over much of the load. This new system had a clear ideological basis, partly derived from the old Academic one. The apparent alienation of the artist from society is really the appearance of a new social framework to provide for him.” (‘A New System Emerges,’ 95)

Written in 1965, this sentence seems to anticipate future scholarship dedicated to the Impressionists and their predecessors. Robert Herbert’s Impressionism: Art, Leisure and Parisian Society and T.J. Clark’s The Painting of Modern Life—currently with over 1,000 known citations—both emphasize the alienation of the artist from society. This passage in Canvases and Careers is a largely overlooked (preemptive) challenge to that focus.

The choice to discuss “alienation” in the second passage presented is a clear nod to Marxist analyses of history. In this passage, the Whites also engage—if not totally explicitly—with Marxist questions and vocabulary. The Impressionists’ own dedication to a bourgeois identity is at odds with stereotypes of artists as bohemian characters. This discussion of the importance of middle class standards also reminds scholars that artists’ poverty was not necessarily equivalent to that of the proletariat. Artists existed very much within the bounds of class and status; they were not necessarily the archetypical romantic genius (like Vincent van Gogh) whose creativity thrived in poverty. This reminder of the artist’s position on the social ladder allows for a better understanding of his or her financial motives and perhaps economically strategic artistic choices.

“Any picture of the Impressionists as living at a laborer’s standard, of course, is not true. What is true and significant is that they were paid, as most painters (and writers) are, on a manual piecework basis—that is, a lower-class bases; at the same time, their backgrounds and their aspirations decreed that they adhere to a middle-class standard of living. A painter is a learned professional—and a learned professional is middle class.

This middle-class standard meant steady support for one’s family, dignified, reasonably furnished living quarters, and at least one servant; it meant decent middle-class clothing, good food served in the dining room with a white tablecloth; it meant the ability to entertain guests and to buy a train ticket to Paris from the suburban town where one lived. The tension between this standard and the unpredictability and insecurity of the Impressionists’ income caused a genuine anguish.” (‘The Impressionists: Their Roles in the New System’, 129)

Even fifty years after publication, the Whites’ book is a methodologically innovative work that continues to provide relevant contributions to debates about art and its relation to social and economic changes during the nineteenth century.

For other installments of “Resource Rewind” see here.

Single-Collector Museums, an Important Source >>

<< Resource Rewind: The Embarrassment of Riches