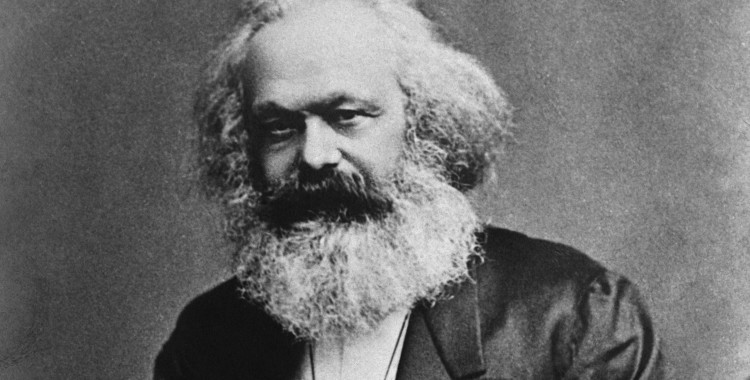

What About Karl Marx?

April 02, 2015

by Diana Greenwald | Filed in: Interdisciplinary

In the opening pages of The Social History of Art (1951), Arnold Hauser discusses prehistoric cave paintings. About these works, he asks, “What was the reason and purpose behind this art?” Hauser’s answer to this question begins with a description of the economic setting in which the cave paintings were created. “We know that it was the art of primitive hunters…who had to gather or capture their food rather than produce it themselves.” Throughout his multi-volume century-spanning study, Hauser continues to ask similar questions and begin his answers with descriptions of contemporary social and economic context. Hauser defined his approach as “social history of art”; he was also a Marxist.

Following in Hauser’s footsteps, self-identified Marxists authored most of the early and influential studies of art and culture from an economic perspective. Raymond Williams’ Culture & Society, T.J. Clark’s The Absolute Bourgeois and historian E.P. Thompson, who wrote The Making of the English Working Class and William Morris: From Romantic to Revolutionary. What is the role of Karl Marx in today’s studies about the arts and economics? His role is certainly less clearly declared by scholars—most of who no longer identify as Marxists—but his legacy endures.

Existing economic and social studies of artists often oscillate between focusing on two distinct elements (as defined by Marx) of any person’s role as a social and economic actor. They explore either the relations of production—defined as specific conditions of transaction—or the mode of production, the totality of a feudal or capitalist society. (Feudalism and Capitalism are the two major modes of production that Marx identifies as existing prior to Communism, the ultimate and final mode.) The artist’s work can either be understood as the output of an employee fulfilling a contractual agreement with his patron or as the expression of disillusionment with capitalist society. The existing literature does not successfully account for how these two identities affect and inform one another. Either an analysis is a tightly focused study of prices and markets or a sweeping examination of abstract perceptions of cities, railroads or other industrial phenomena. A middle ground is missing. Art historian Linda Nochlin—a pioneering contributor to the social history of art—wrote in The Politics of Vision (1989): “The difficult or thorny issue of mediations is, understandably, often sidestepped by the social history model, leaving a heap of historical or social data on one side of the equation and a detailed analysis of pictorial structure on the other, but never really suggesting how the one implicates the other, or whether, indeed there is really any mutual implication.” How can a scholar respond to Nochlin’s criticism? There are many possibilities, and with this question in mind Arts & Econ will highlight several emerging methods and approaches over the next several weeks