Automating Connoisseurship, a Conference Response (Part 2)

May 11, 2018

by Diana Greenwald | Filed in: Conferences

This post is part of series of responses to themes addressed at the Frick Art Reference Library’s symposium “Searching Through Seeing” Optimizing Computer Vision Technology for the Arts,” which brought together art historians, computer scientists, engineers and business people.

How can we be sure that art is authentic—that it was created by a certain artist at a certain period? This issue is consistently in the media (most recently about a small museum in France) and has previously been discussed in a philosophical framework on this blog. However, the presentations at the Frick Symposium raised new issues about connoisseurship and authentication, and how technology may have a significant role to play in verifying whether or not a work is genuine.

The focus of the conference was computer vision, and many of the presentations described how computers, aided by neural networks and deep learning, are getting better at recognizing patterns in images and matching like with like. This was affirmed in presentations by big companies like Facebook and IBM, art-specialized enterprises like Artrendex founded by Rutgers Professor Ahmed Elgammal, and university-sponsored projects like the English Broadside Ballad Archive. While still in the early stages of application to the arts, there was near consensus among presenters that computer vision could aid in a risky task the art world has long been forced to confront: the authentication of valuable works of art.

Connoisseurship and authentication have been progressively less present in art historians’ training since the mid-twentieth century. Today, there is a split between the more theoretical and thematic analyses of academic art historians and an increasing reliance on technical art historical studies to aid in authentication. This article from the Getty summarizes the development of that split and how central training in connoisseurship used to be to art historical education. As described in the MIT Technology Review, computer vision seems poised to be the latest technical development that can place connoisseurship further beyond the realm of academic art history.

What are the economic implications of the transfer of connoisseurship from humans to machines? There is an evident advantage of this change, as an art historian in attendance described, is linked to litigation. Art historians who agree to authenticate art open themselves up to potential litigation if their professional opinion is later proven to be incorrect, or if people are unhappy with having their artwork declared inauthentic. However, this perceived advantage is dependent on the computer vision being more reliable than human vision and expertise—and it is not yet clear this is the case. As all the presenters noted, training a computer program—which is, of course, designed by humans—to recognize artworks depends on enormous amounts of high-quality data annotated by humans. Because it is technological, computer vision has the trappings of providing an objective and definitive “Yes” or “No” on authenticity. However, it is neither infallible nor free of the human intervention that has proved problematic in connoisseurship in the past.

While it is promising, the push for computer connoisseurship is just the latest in a long line of art world phenomena that aim to justify the value of a given work of art. It is part of a search for certification in a market where reliable information can be scarce.

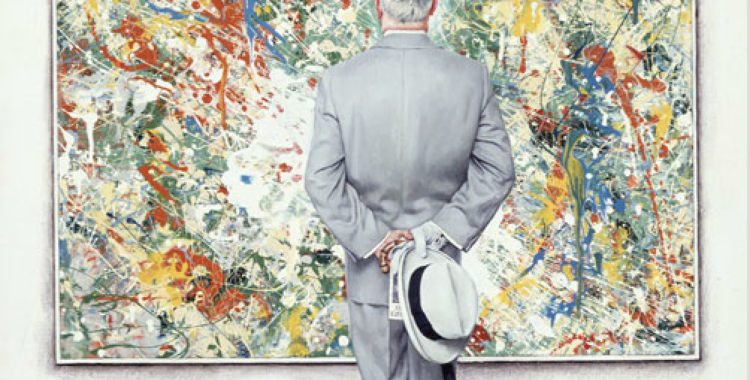

Image Credit: Detail, Norman Rockwell, Art Critic, The Connoisseur, 1961. Cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, January 13, 1962. https://www.nrm.org/2012/09/rockwell-and-realism-in-an-abstract-world/

<< The Power of Art to Sell, a Conference Response (Part 1)