The Power of Art to Sell, a Conference Response (Part 1)

April 18, 2018

by Diana Greenwald | Filed in: Conferences

Traditionally, this website has addressed the overlap between art and economics from an academic perspective. It has applied theories of taste to politicians, discussed cultural omnivores and mined insights provided by academia. On April 12thand 13th, the Frick Art Reference Library’s Digital Art History Lab hosted a two-day symposium on the application of computer vision—and computing more generally—to art history. Called “Searching Through Seeing” Optimizing Computer Vision Technology for the Arts,” the conference brought together art historians, computer scientists, engineers and business people. The interactions of all of these different constituencies invested in the application of computing technologies to art history were fascinating. This post—and the following two over the coming weeks—will address questions raised at the symposium.

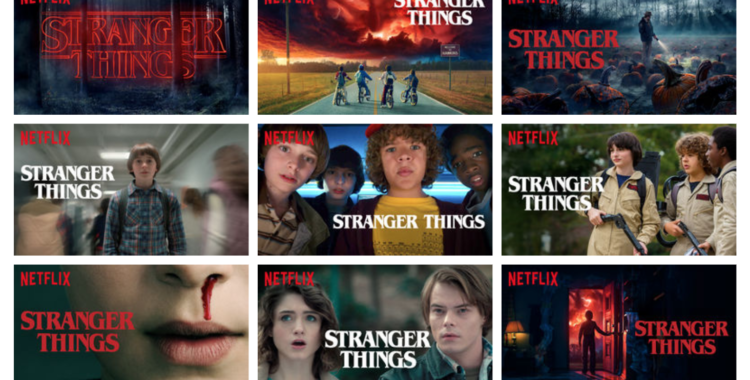

In her talk on using machine learning to develop personalized taste profiles for clients, Sotheby’sExecutive Vice-President Jennifer Deason provided examples of computer vision already in action. She cited Amazon’s X-Ray feature on Prime Video and then discussed Netflix. Her discussion began with a slide showing a standard Netflix homepage stripped of all its images—and therefore only displaying the title text of recommended shows and movies. Deason went on to describe how Netflix personalizes the images accompanying its suggestions based on viewers’ recent watching behaviors. Goodwill Hunting (1997) can, for example, be shown with an image of Matt Damon and his romantic interest, played by Minnie Driver. This image would be selected for viewers with a proclivity for romance. For viewers that prefer comedy, an image of Robin Williams (who plays the protagonist’s therapist) appears in the thumbnail for Goodwill Hunting. In short, Netflix optimizes the imagery associated with suggested viewing to please its users. It adapts the visual summary of a show or movie maximize appeal.

This quick example demonstrates something that most artists and art historians already new: images resonate with audiences and can quickly communicate ideas and emotions. However, this power of art is repurposed in the Netflix example for real-time adaptable selling. Where a user clicks, or not, can be molded by images a website feature. In this setting, art and images are not simply a product of social and economic context but are driving economic consumption.

This simple Netflix example was a reminder of how visual imagery has long been deployed for commercial uses—consider the research of Leigh E. Schmidt on the commercialization of holidays Jennifer Greenhill’s on-going research about commercial illustration in the mid-twentieth century. However, what is novel is the potential for personalization. While advertisers and designers had to make a judgment call about what image would appeal to the broadest possible audience, a digital format and recommendation algorithms make it possible for commercial designers to tailor images to each user. In short, the aesthetic attraction of given images can be deployed even more effectively to make users click, engage and—ultimately—purchase or continue to subscribe. In the digital age, art—or at least visual imagery—will become a more effective vehicle for commerce than it has ever been before

Automating Connoisseurship, a Conference Response (Part 2) >>

<< As Seen on TV: Thoughts on Art Exposure Through Television