Guns, Germs, And Gothic

April 16, 2015

by Diana Greenwald | Filed in: Interdisciplinary

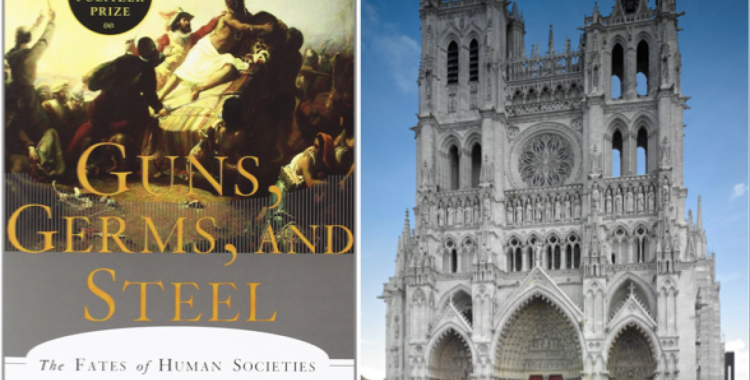

Jared Diamond—Professor of Geography at UCLA—argued in his Pulitzer-Prize-winning book Guns, Germs and Steel (1997, see Chapters 13-14, 16, Epilogue) that one major determinant of how a society develops is its openness to innovation. Diamond’s theory aims to explain divergent patterns of agricultural advancement and industrialization around the world. He and other contributors to the study of the “Great Divergence”—the gap between countries able to overcome pre-modern growth constraints in the early 19th century and those that did not—focus on obviously productive technologies like farming equipment and steam engines. However, applying Diamond’s theoretical lens to art and architecture—less clearly productive technologies—may be a fruitful exercise.

The elements of Diamond’s book that focus on innovation lean heavily on vocabulary taken from Evertt M. Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations (1962), which distinguishes between “Innovators”, “Early Adopters”, “Early Majority”, “Late Majority” and “Laggards.” It is possible to divide groups of artists and patrons into these categories for artistic and architectural innovation. One experiment in applying these categories to art history could be an analysis of the study of the spread of Gothic architecture in Northern Europe from the 12th to the 15th centuries.

Mapping Gothic France is a project that—as the name suggests—maps the spread of Gothic architecture in and around France. From the innovations of the Abbé Suger at Saint-Denis to the early adoption of the style at Lincoln in England—despite the physical distance between it and the birthplace of Gothic—and the surprisingly late adoption of the style at Orléans. One can ask the same questions about the spread of architecture across European communities that Diamond asks about the spread of agricultural and technological innovation across continents. What drove this chronology of Gothic’s geographic distribution? Is it the chance arrival of a particular architect or patron, or is there something intrinsic to the communities that quickly chose to start building in the Gothic style? Why did they take a risk on a significant formal and structural departure from earlier Romanesque buildings?

Answering questions like these may not only be useful for art and architectural historians, but for economic historians. Literature about economic development often compares England and France, to the disadvantage of the French. However, the central role of France in the development and diffusion of Gothic architecture—one of the most significant accomplishments of the pre-modern engineering—could provide a caveat to this entrenched narrative.

Arts & Econ Wants You… To Write For Arts & Econ! >>